Beethoven A Major Cello Sonata Program Notes

Program Notes Beethoven Chamber Concert Series, Year IV Concert IV - March 30, 2014 Violin Sonata No. 10 in G Major, op. 96, “The Cockcrow” If there were any logic in the way that popular musical compositions get nicknamed, Opus 96 would be known as the “Archduke” Sonata, by analogy with its companion piece, the “Archduke” Trio, Opus 97. Beethoven composed both works in 1812, delayed publication of both until 1816, and dedicated both to his student and patron, Archduke Rudolf. Both pieces also occupy an interesting position on the cusp between what has traditionally been called “middle period” and “late period” Beethoven. Though they grow out of the lyrical side of the composer’s musical persona, they already anticipate the more compact forms of the later years. And they downplay strongly asserted, dramatized conflicts of opposing keys, the characteristic that in the popular mind is synonymous with the image of the “two-fisted composer.” The opening movement of Opus 96 is marked Allegro moderato, and its character throughout is songful.

Few large sonata compositions have ever begun with such an unprepossessing, even offhand, beginning as the first phrase of this work, a little warm-up phrase for the unaccompanied violin. Psp Cricket Game Iso. But the piano echoes it at once and both instruments extend it in an expansive, unhurried cantabile. Expansive in feeling but brief in extent, for soon Beethoven engineers an entirely straightforward--almost perfunctory--modulation to the dominant, where the piano introduces the secondary theme in a dotted marchlike figure over triplets in the violin. Crack Para Simplecast 3.1.0. Now comes the surprise: the presentation of the two principal thematic ideas of the movement has occupied nearly sixty measures, yet we gradually discover that we are only two-thirds of the way through the exposition.

Beethoven creates a surprising expansion at this point with harmonic digressions and feints at closure. But in fact the exposition runs seamlessly into its own repetition (the first time) and then on into the development (the second time) without a firm cadence. The development section, too, remains lyrical in character, with little sense of the dynamic and aggressive search for the home key that characterizes, say, the Eroica or the Fifth symphonies. In fact, we are poised on the threshold of the home key and anticipate its immediate return when Beethoven suddenly draws back to sidle home quietly eight bars later, as if he no longer needs to hit us over the head with the power of the return home, but simply wants to emphasize its utter naturalness. The recapitulation is anything but a simple rehash of the exposition; after a single phrase in the home key of G, it moves off to the submediant, E-flat, to balance a similar move in the exposition (and, incidentally, to anticipate the key of the second movement). But this harmonic adventure necessitates a more elaborate transition to bring the secondary theme back finally in the home key, and justifies the lengthy coda. The songful slow movement, in E-flat, is progressively decorated in both violin and piano, but never loses sight of its melodic origin through all the imaginative changes of texture.

The third movement is a Scherzo and Trio, analogous to the corresponding movement in a symphony. This one, though, is in G minor, a surprising occurrence in a composition based in the major.

(From Haydn’s time it was common to have the Trio turn to the minor mode, but the Scherzo itself was almost always in the key and mode of the work as a whole. Here, though, the Scherzo is in G minor, while the Trio takes up once again the key of the second movement, E-flat, which had also appeared prominently in the first movement.) The last movement has a special character that comes as something of a surprise. It has none of the quality of “triumph after torment” that we so often associate with the typical image of Beethoven. Its discontinuities—changes of tempo from Poco Allegretto to Adagio espressivo to Allegro, finally closing with a brief Poco Adagio—suggest some of Haydn’s “joke” endings.

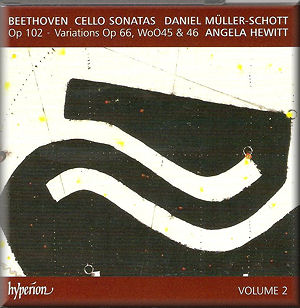

Cello Sonatas Nos. 4 and 5 (Beethoven). It concludes with an elaborate cadence in C major that is then contradicted by the sonata portion being in the. LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN’S SONATA FOR CELLO AND PIANO. Program of my first D.M.A. Recital in 2010. THE ANALYSIS OF BEETHOVEN’S CELLO SONATA IN F MAJOR OP. TheAMajorSonata (1808) iswritten. Cello Piano Inthesecondtheme,Beethovenagainmakessmallsuggestionsthroughthetensionand. PROGRAM NOTES Sonata in A Major, K 24 –Scarlatti. Sonata form developed later by Haydn and Mozart and perfected by Beethoven. Of these he left.

But here there was a specific extra-musical reason for the character of the movement: Beethoven was composing it with a specific violinist in mind, Pierre Rode, a Frenchman and a fine player who gave the first performance of the work with the Archduke. As the composer explained to his patron in a letter: “I have not hurried unduly to compose the last movement merely for the sake of being punctual, the more so as in view of Rode’s playing I have had to give more thought to the composition of this movement. In our Finales we like to have fairly noisy passages, but R[ode] does not care for them—and so I have been rather hampered.” Out of necessity, then, Beethoven crafted a most unusual movement, combining the character of a rondo at moderate tempo with elements of variation, all presented with elegance and grace. Crypkey Site Key Generator Crack there. - Notes by Steven Ledbetter Cello Sonata No.